Who’s in charge of family traditions? Who decides when something becomes a tradition, and who decides when it’s time to leave a tradition in the past?

Most of us would look to our elders to answer these questions – maybe our parents, or maybe our grandparents if they’re still with us. But in her twenties, author Nadine J. Cohen and her sister became the oldest surviving generation in their family after their Nanna Dina passed away. Nadine’s parents had both already died, leaving her and her sister to care for their Nanna.

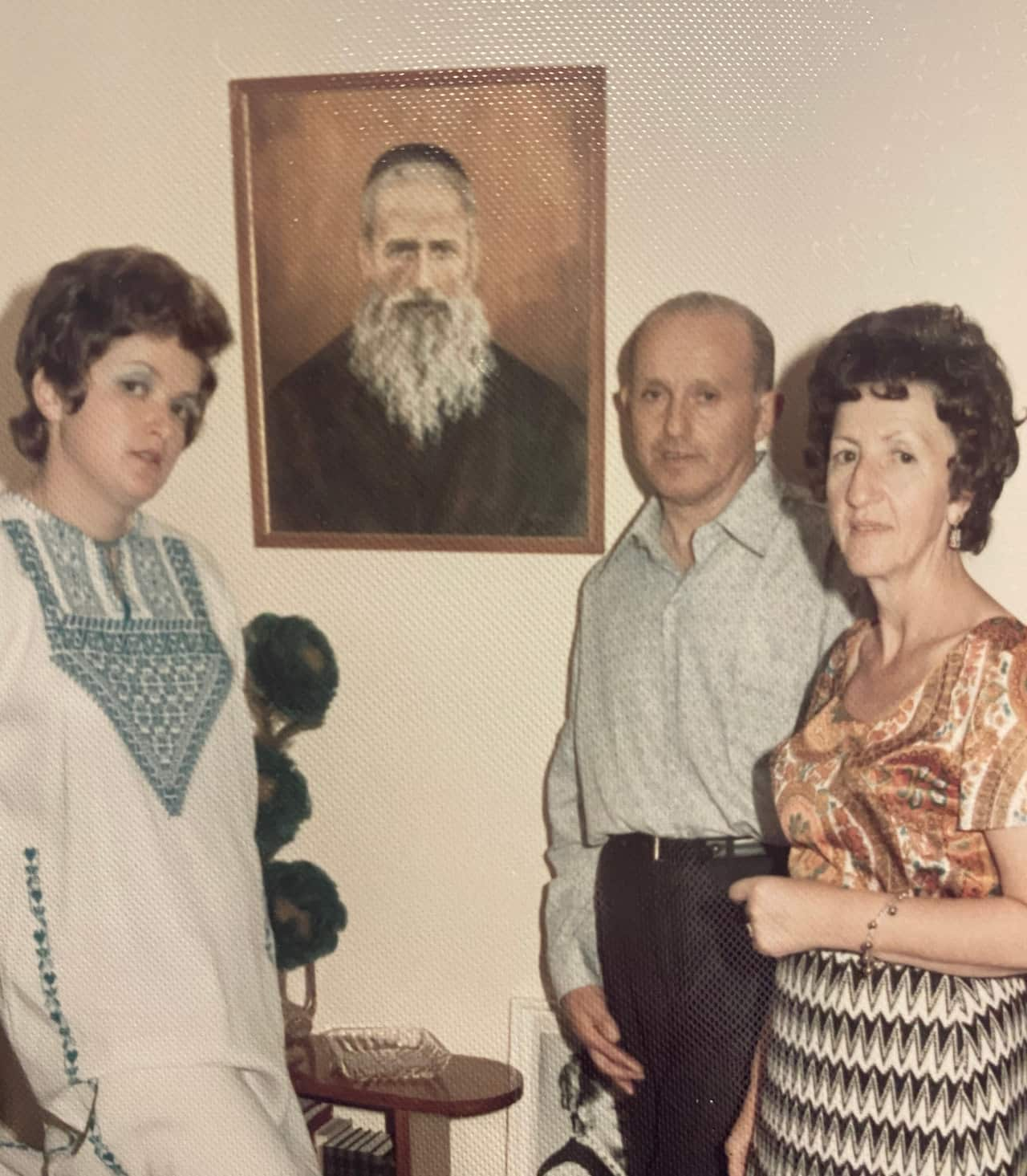

Nadine's mum, Zeida and Nanna

Nadine's Nanna and Zeida at their milkbar

Dina struggled with her mental health throughout her whole life, doubly so given mental health was poorly understood and barely talked about for most of her life. But Nadine, who herself has also battled mental health issues, is sure her Nanna understood their unique connection. “They don’t understand people like us,” she would say, but Nadine and Nanna understood one another.

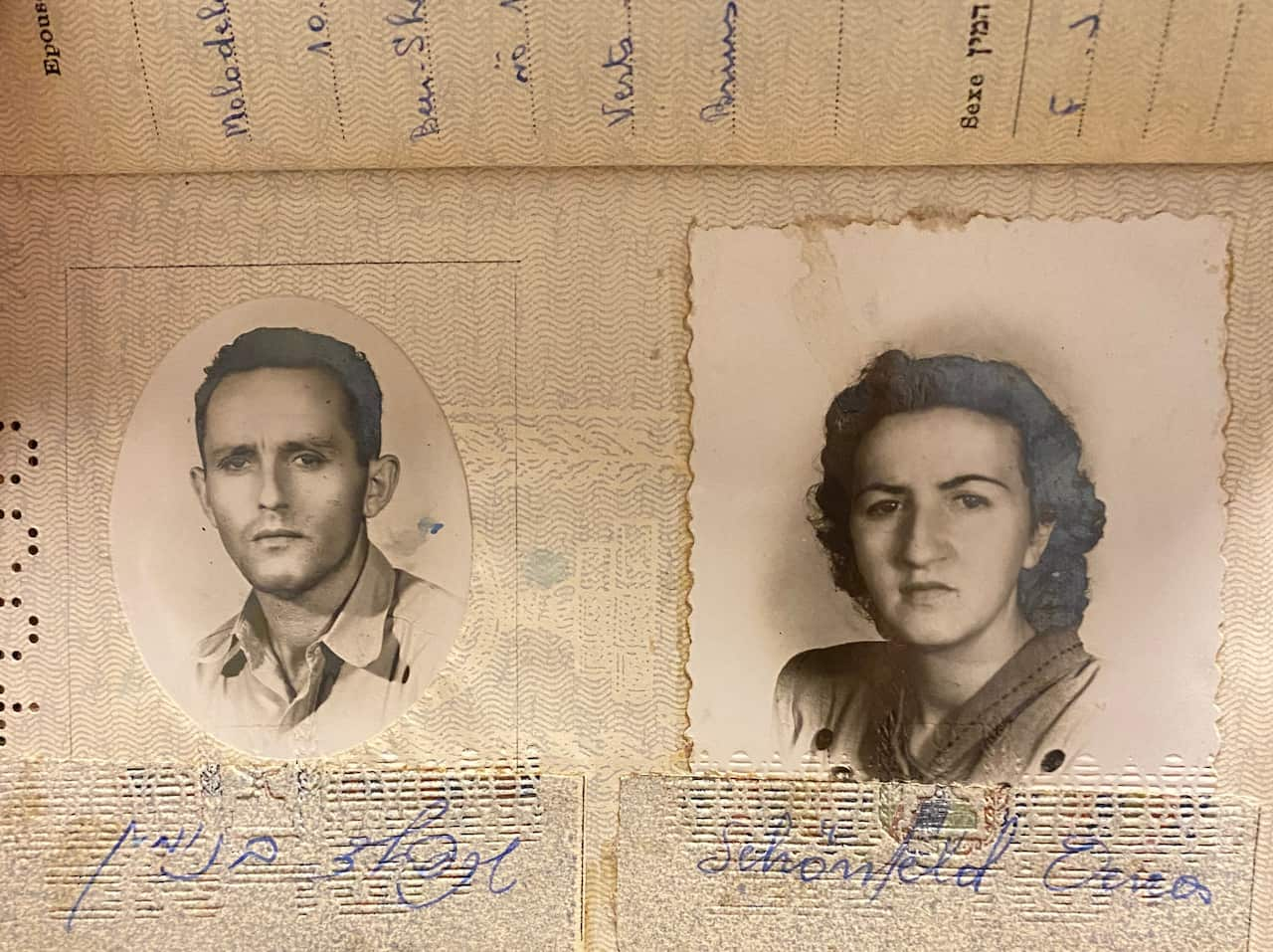

Ben and Dina's passport photos when migrating to Australia

I remember one of my friends saying to me when my mother was ill, and I was her full time carer and I was having a hard time - 'You know you don't have to do it'. I was shocked. I think that's partly an ethnic thing... there's no choice, you just look after them. Mum died, so we looked after Nanna. There was never any doubt or any questioning.Nadine J Cohen

LISTEN TO

Role reversal: Nadine J. Cohen reflects on becoming her Nanna’s carer

SBS Audio

01/08/202435:06

Thanks to Nadine J. Cohen and the Sydney Jewish Museum for providing the audio recordings of her Nanna Dina that are used in this episode with permissions.

Executive Producer: Kellie Riordan

Supervising Producer: Grace Pashley

Producer: Liam Riordan

Audio editor and sound designer: Jeremy Wilmot

SBS Audio: Caroline Gates, Joel Supple, and Max Gosford

Artwork by Universal Favourite

We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Australians and Traditional Custodians of the land on which this show was made.

Transcript

Note: This transcript has been automatically generated.

I'd like to acknowledge the traditional owners of the land I'm recording from.

I pay my respects to the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation and their elders past and present.

I also acknowledge the traditional owners from all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander lands you're listening from.

Just a quick heads up, this episode speaks about the Holocaust and mental health.

Please take care while listening.

I remember one of my friends saying to me when my mother was ill and I was her full-time carer, and I was having a hard time.

And I remember one of my friends saying, you don't have to do it.

And I was shocked.

And I think that's partly an ethnic thing.

There's no choice, you just look after them.

So we looked after Nana.

There was never any doubt that we'd do that or any questioning.

It was very difficult.

Nadine J.

Cohen is fascinated with the complicated, messy and kind of dark things that make us human.

She untangles family webs and mental breakdowns in her novel, Everyone and Everything, and explores death and grief in her SBS podcast, Grave Matters.

They're heavy subjects, but as the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, she's well equipped to deal with them.

I'm Lizzy Hoo, and this is Grand Gestures.

Nadine spent her childhood running around the parks of Sydney's eastern suburbs, while her Nana and Zeida watched on, playing cards with their friends in the local Jewish community.

It was a world away from the horrors that escaped after surviving wartime Poland in the 1930s.

The memories of the war never really left Nadine's grandparents, but there were happier times, too, when Nana was a girl living on an apple orchard.

Nana always talked about her childhood very fondly.

I think it was a childhood full of love.

It was, yeah, rural Poland.

I don't even know, like, I think there was a town near, but it was, you know, the next, you know, farm or house was very far away.

She attended school until war broke out.

She had an older sister and an older brother, and they were all very close.

Her mother was, I think, I think a homemaker and tended to the orchard and the farm, and then her father was a traveling salesman of some kind.

She only got a bit of a childhood.

The war broke out when she was 10, and then all hell broke loose from there.

What were the war years like for her?

Harrowing, horrible.

When war broke out in 39, she was 10, and they were the only Jewish family in the community, and the community had previously been very welcoming of them and very accepting of them.

And so when war broke out, her parents hid her with another local family because she was blonde and she could pass as Polish, whereas her sister had very dark curly hair and very dark features and was quite clearly Jewish.

Nadine's nana told her story to the Sydney Jewish Museum before she passed away.

And she remembers fleeing when the war broke out, a moment that stuck with her right up until the end of her life.

They were under the orders to take us away.

And somehow, like a premonition, the mother, she said, I don't feel safe.

And when the SS were following the wagon, my mother just put her head down and cried, wouldn't pick up her head.

And my father said, it was like half this time, the fields were all high.

He said, jump.

I jumped right away.

They were shooting and went door but didn't find me.

So a local family agreed to take her in and hide her, which they did for some time.

I came to a certain place, which I knew they will help me.

He came and he said, I will have to look for a place for you somewhere.

But it didn't last that long.

Once like rations and like once life became really hard, they kind of were focusing only on their family and they didn't have enough for her.

They also stole a lot of her things that her mother had left with them.

She was never in a concentration camp, but her war story is a story of kind of hiding in different places between houses.

Her oldest sister was living in the forest, which was a thing that Jews did.

And sometimes the armies would know they were there and either bring them food or brutalize them, depending who was.

And her brother was fighting for the resistance.

Her older brother and her older sister would come back as much as possible to try to make sure she was okay.

And all three survived the war, which is almost unheard of.

Her parents, however, her father died at Auschwitz and her mother died.

So she got shot on the way to Auschwitz.

And so, yeah, like her war years were basically hiding.

She talks about being covered in, you know, lice and fleas all the time.

One thing she never talked about specifically was kind of, you know, she was a young girl and very vulnerable and, you know, things were done to her that she never spoke of, but we knew that, you know, that had to have been the case.

So your Nana has just lived through these horrific war years at a really young age, and she meets your grandfather, Zeida Ben, pretty soon after the war.

What was their relationship like?

I think after the war, especially Jews were just finding each other and starting new lives.

And it was like, we've got to all marry and start having new children and replace what was lost in a way.

But also, yeah, Nana was, I mean, she was 16, I think, by then.

Her older brother and sister had partners and so they wanted someone to look after her.

She was still a child, but he was 35 at the time already.

I didn't ask his age.

I didn't have a clue what a man is.

And he came a few times.

I went a few times to his friend's place and all that.

And in three weeks' time, they put a marriage together.

He looked very good.

I didn't think he's...

After the wedding, could I learn how old he is?

I cried myself half a year.

I just thought about it, just there.

But he was very good to me.

It was just another thing in her life that she couldn't control.

So Nana and Ben are married and trying to start their lives after the incredible trauma of the Holocaust.

And they fall pregnant with your mum.

What was early motherhood like for you, Nana?

It was difficult.

I think she had my mum, she was like 18 maybe or 19.

She didn't know what to do with a child.

She didn't have anyone around her to tell her.

Her sister had a child two weeks after my mum was born.

But my grandmother was very, she was very mentally challenged in a lot of ways or mentally unwell.

And over the course of her life, she had certain breakdowns.

And I know that she had one soon after my mum was born.

And so I think that was very difficult.

But when my mother was six months old, they got out of Poland and they were in a internment camp in Italy for, I think, six months as well.

There are a lot of Jewish refugees that were in Italy.

And my grandmother didn't produce milk.

And I don't know if that was a mentally unwell situation, if her body had just shut down.

Her body had also been very brutalized and not just sexually.

She was with one of the families that she was hidden with when the donkey died.

She acted as like the cart horse.

So her body was just like a mess.

And so her sister ended up breastfeeding my mother because she had had a child two weeks later.

So I think it was a really difficult and confusing time.

Yeah, having a child in a tent in Italy, in a foreign country just after the war must have been incredibly difficult.

So Nana, Zeida and your mum started their journey out of Poland.

They followed the beaten path of many other displaced Jews at the time and settled in Israel.

But then how did they end up in the eastern suburbs of Sydney?

Yeah, they went to Israel from Italy and there wasn't a lot there.

It was a very fraught time and there wasn't a lot of work and there wasn't a lot of money to be made.

And my grandmother's sister had come to Australia a few years earlier.

She wrote and said, you can find work here, it's the land of opportunities.

Both my mother's family and my father's family arrived in Australia in 1956.

My father's family, however, were from Egypt.

They were Russian, but they'd been in Egypt for several generations.

And they got kicked out of Egypt in 56.

And so they both like coincidentally ended up in Australia at the same time.

So they just ended up here because it was a time of opportunity.

Bondi, Bronte and Waverley are still famous for their strong Jewish community.

How did that help them settle in when they first moved?

I think it definitely helped them set them in.

Someone got my grandmother a job as a seamstress in a sweatshop, basically.

A lot of Jewish women worked in sweatshops.

And my grandfather, someone else got my grandfather a job, I think, cleaning.

After a while, they saved their money and they opened two, like it was called like mixed business or milk bars.

It was the typical immigrant corner shop we would call it now.

And they had two and they lived behind the one in Waverley Bronte.

And what was their apartment like?

It was a very typical, I would say ethnic grandparents' house.

You know, overly formal, but then like plastic covering things and a bit of a hodgepodge of furniture and no, no riches.

Like there was some silverware, I think, but there was nothing kind of fancy.

But it was a really beautiful home.

And you know, I remember it very, very fondly.

I mean, she only moved out of there 2008, 2009.

So she was there for 45 years.

I used to pick them up Friday from school and take them to my place.

I had them till Saturday night.

So it was hair washing and pyjamas throwing and whatever.

So Friday nights were particularly special in your Nana and Zeida's house.

Why is that?

So Friday night, we would generally do what's called Shabbat or Shabbas, which is, you know, many people have heard of it as Friday night dinners.

And it's for the Sabbath.

And if you're religious from sunset on a Friday to sunset on a Saturday, you don't use electricity.

You'd like, there's a lot of, like you say prayers, you don't really do much.

It's a quiet time.

It's a time of reflection.

We were not a religious family at all.

But when I was a kid, we did Shabbat.

We did Friday nights with my grandparents.

And my sister and I would stay at Nana and Zeida's.

And what would you get up to?

Nana and Zeida would go to bed, to their separate bedrooms, early, like 7 or 8 PM, like they would be asleep, or at least in their rooms.

My sister and I would be left in the television room with our mattresses on the floor.

And every Friday night in the 80s, there were AO movies, which were adults only, which is now R.

But I think AO was, like I think they were slightly different to R.

It was mostly a sexual thing, like the violence wasn't so much a thing.

And this is like the 80s movies of, you know, they're all tits and ass in 80s movies.

They're all so misogynistic.

And my sister and I would watch these movies every Friday night at like age like 8 and 10 or something.

And then my parents started realising, because one would, there'd be an ad for one, and areola and I would be like, oh, that's the one with, with, with that.

My parents were like, what have you people been watching?

That's amazing.

Do you remember any of the names of the movies?

Yes, I can.

Bikini Shop was a big one that we loved.

Bachelor Party, which is a little known Tom Hanks movie.

Like I think it's his Bachelor Party and it's very, very smutty and horrible.

There were like a couple of The Revenge of the Nerds, which were really, you know, super misogynistic movies, like that realm of movie.

Did you ever get properly found out?

Yeah, like eventually, like mum and dad were like, oh, but we were older by the time they found out.

So it was kind of like, what's done is done.

My grandparents, I don't think ever knew.

Apart from the movies, how else did you spend your time with Nana?

Nana was a very, very involved grandparent.

She learned to drive to help my mum with us, and she did school pickups and we'd stay with her.

There'd be a lot of playing cards.

They loved playing cards.

So Polish Rummy was the card game that they played, and that's what they played in Centennial Park with the Polish Jewish community there.

Nana loved soap operas.

So we watched a lot of days of our lives, and Young and the Restless, and Bold and the Beautiful.

And we'd go for it.

Like she'd take us on a lot of walks.

She'd take us to the park.

Like just typical, very typical, except for the soap operas, very quite typical grandparent stuff.

She was quite young.

Like my grandmother was only 10 years older than my father.

You know, she had my mom so young.

So she had a lot of my, my grandfather was so much older, but she had a lot of life in her when we were kids.

Your Nana and Zeida had survived so much together before they arrived in Australia.

What are your memories of him?

Look, he, they're very beautiful and warm, but he did not give much of himself.

He, you know, it's not that he barely talked about the war, he barely talked.

And, you know, I have memories of like him bouncing me on his knee and singing Polish nursery rhymes to me.

But my main memories of him are silence.

And it wasn't like an angry or imposing silence, it was just, he doesn't speak much.

His English was never that great as well, and because I think he didn't speak enough for it to be.

But, you know, he was a very kind and gentle man.

And that bled out to other people as well.

A couple of months ago, my sister in a Facebook group, someone posted a photo of my grandfather at his shop and said, you know, does anyone remember Ben at the Bronte mixed business store?

He was such a lovely man.

And my sister just happened to see it in like a local, one of those loop groups.

And she was like, oh my God, like, that's my grandfather.

And we sent him some other photos of my grandmother.

I think his kindness reverberated beyond our little family.

So you grew up as quite a close knit family with your parents and grandparents, which must have made things even more difficult when your parents' health started to decline.

What happened?

Yeah, so my father had dementia.

He was diagnosed at 59 and he passed away at 62.

And that was obviously a horrible time.

Watching anyone with dementia is difficult.

Watching your relatively young father go through it is harrowing.

But he died and then three months later, my mum was diagnosed with breast cancer.

And so I was 22 when he died, and she lasted 21 months.

And then she died on the Jewish anniversary of his death.

At the same time, which is just a beautiful thing that I, you know, I'm not a religious or a spiritual person, but it's just a nice thing.

And then my grandmother was still alive, and she was in her mental health amenities by then.

And so then my sister and I were responsible for her.

She was, you know, an older woman, but her physical health was pretty fine, but her mental health was very poor, and she had, you know, obviously complex PTSD from what she went through as a child.

And then she had bipolar.

She started to get dementia.

And so it was very much more about her mental care than it was about her physical care.

So what did that look like on a day-to-day basis for you?

It changed over the years.

At first, it wasn't so bad.

And she was still living in the Waverley apartment and she was quite independent.

She had a car, but eventually we got her a carer, just who would come two days a week and take her to the shops and things like that.

But she was pretty good.

And then it just kind of started to unravel a little bit.

And we moved her into a like assisted living but not full care environment.

So she was still very independent.

She could still do a lot of things, but she couldn't drive.

There began to be restrictions on her movement and her life.

And then for the last year, she was in a home.

And yeah, it was very challenging.

For the last year or two, I would say I saw her every day, if not twice a day.

As would my sister, because she was so fraught and just scared.

And my father's dementia, it was horrible.

But a lot of the time, he was in a happy place.

I'd say, how are you dad?

What's going on?

And he would say, I went for a walk with Johnny this morning.

And I'd be like, okay.

And Johnny had died 10 years ago.

There were bad times, but he was actually in a nicer place.

Whereas my grandmother went to the Holocaust.

Like she went back to her childhood in her dementia and was very scared and men couldn't come near her.

She was very scared of men, which made caring, like the home, caring for her hard.

And just got to the point where the, like my sister and I were the only ones that could kind of calm her.

You know, I had to work, I had to earn a living.

We're not a rich family.

And trying to navigate being a carer for her and making living was a very difficult time, especially for that last year.

Did you feel like you had a choice in that, or did you sort of just naturally, you just did it?

Yeah, no, there was no question.

I remember one of my friends saying to me when my mother was ill and I was her full-time carer, and I was having a hard time.

No, I remember one of my friends saying like, you don't have to do it.

And I was shocked.

And I think that's partly an ethnic thing.

Like there's no choice.

You just look after them.

Mum died, so we looked after Nana.

There was never any doubt that we'd do that or any questioning.

It was very difficult.

And yeah, it wasn't anything I would have done over.

And what were your nana's final years like?

They were really tough, you know, mentally again.

She became quite paranoid in some ways.

You know, me and my sister, you know, at times like accusing us of stuff, which was really hard because we were trying so hard to help her.

I wish I could say they were great, but they just weren't good times.

I mean, my sister had two small children by then.

She was pregnant actually with her third when my grandmother died, but she really delighted in the kids.

Like it was really lovely to see her with the kids, but she was hard.

She was demanding and quite difficult, but you just look at her and just like, just go, of course you are.

Like her beginning of life was just so bad.

She would be being not very sympathetic to me, and I had just lost my mother.

And then I would look at her and I would be, I would want to scream like, I just lost my mother.

But then I was like, your mother got shot on the way to a concentration camp.

You're like, she's forgiven for everything that she kind of did in those years.

They look after me now, but it's not forgotten.

They still remember how they used to sit in the tub.

It was very hot and I gave them strawberries to eat in the tub.

I was closer with them than I was with my daughter.

She was always busy or didn't have the patience or whatever with me.

And then when she got sick, it was really...

But we put Nadine through the whole thing.

That contact is never forgotten.

We are very, very, very close.

That must have been so hard, grieving the loss of your parents, then caring for and eventually grieving your nana.

How did you cope with that?

It was pretty bad. Um, this was all in my 20s. And so drinking was, that's how I coped, just a lot of partying and drinking.

My mental health, you know, I was diagnosed with major depressive disorder when I was 19. I look back and I go, oh, I was fine. And that's definitely not true. And I definitely felt very stuck.

You know, it was my 20s. I wanted to move overseas. I wanted to do all these things.

And that was the frustrating bit for me.

I was trying to finish uni at the same time, and I kept having to defer uni and try and work. It was, it was a fraught time. So I think my mental health wasn't great.

But if I kind of jump forward into an overshare, you know, I had a breakdown myself almost 10 years ago. And that was five years after my grandmother had died, 10 years after my mother had died. And I was like, why now?

And I said to my psychiatrist, you know, why didn't it happen back then?

And she said like, this is that. You've been carrying that. And now it's been triggered and something's coming out.

Did your parents and grandparents, I mean, everyone has traumas in their own ways.

Did they ever talk about their mental health with you?

Was that a conversation?

No, my parents really struggled when I got diagnosed with depression with accepting it and knowing what to do about it. All I knew about Nana was that she had had breakdowns. I still to this day don't know what that means. I don't know how they presented.

And when I had mine, I became very obsessed by what it would have been like for her.

Because I had a breakdown in Sydney in 2015. I already had mental health experts.

It happened in a way that I didn't get extra stigma or trauma on top of it. And I think about my grandmother. I think she had one during the war as a kid.

And I think about that.

And then with my mum in Poland and then coming to Australia and having them as a migrant, non-English speaking background woman without much money.

I don't know what that looked like.

And one of the worst things about your parents and your grandparents and everyone dying by the time you're, I think by the time I was 29, is that there's no one to ask of these things when you suddenly think of them.

And I really wish that I had been able to understand more about her mental health.

So that I could somewhat understand mine as well, because it's all intergenerational trauma.

Nana also talked about her own mother as a quote unquote, nervous woman.

And I think her mother must have had anxiety or mental health problems of her own, just from some of the things that Nana used to say and that are there in her oral history that she gave to the Sydney Jewish Museum.

And even she says her mother got shot on the way to Auschwitz, and she thinks her mother probably knew she wouldn't cope mentally and so caused a fuss.

And all these words that were used that I just believe, I think mental health problems extend beyond just the Holocaust.

They go back.

I think she would have probably struggled with her mental health, regardless of her childhood.

What was your life like after your nana's passing?

I think it was really, I mean, I was obviously grieving, but I was also relieved.

It was a very difficult few years.

But also, I had been a carer for seven years at that point.

I realised how hard it was not to have someone else to look after, just because I was so used to it by then.

Also, it meant I had to look inwards.

I remember feeling really lost without that.

Also feeling very young and not having now any elders, I found really difficult.

But over the years, I found myself creating friendships with much older women and doing it subconsciously, and then realising one day, just like, oh, that's what I'm doing.

I want a mother or I want a grandparent.

You and your sister are now the elders of the family line.

So you're kind of in charge of the traditions.

How do you decide which traditions to keep alive?

Um, I am very much, you know, and not practicing religiously Jewish person, but I, I, as I get older, I practice the culture more in certain ways.

And part of that is because my sister and her husband and their kids, again, not religious people, but the kids go to Jewish school. their, their community is mostly Jewish. My community, my friendship community isn't Mostly Jewish. So I don't know. I just kind of do what I'm comfortable with.

You know, it's Passover started last night, which is a big holiday for us. And, you know, I took part in the big dinner and ceremony that we do, but for the next eight days, you're supposed to not eat yeast and things that rise in certain grains.

And I'm like, I ate bread this morning, that I don't keep that stuff up.

But I like to do the things that I think mum and dad would have liked me to do.

Like there's a, every year, there's a prayer for the dead on the holiday.

And each synagogue reads out the names of past members of the community, of the congregation.

And I try and go to that for my mum and dad, because not because I feel solace in it, but I know they would have liked that.

Yeah.

Your nana has such an incredible story, and she sounds like such a resilient person.

Are there any traits of hers that you see in yourself?

Yeah.

I think that my progressive values and my lefty values, which weren't necessarily my parents' values, they're definitely formed by her.

She was much more progressive and liberal than my parents were.

I remember walking into her house one day and hearing her shouting.

I was like, what the hell? I ran to the TV room mostly where she was.

She was getting angry at the mid-day movie because the son of a family of a father was coming out to his parents, and they weren't having a bar of it. She was like, it's natural.

Let them be.

Which I just loved, and I think it's in those values that I feel closest to her.

I feel like she had the most influence in me.

Then again, in terms of mental health, because we didn't talk about it that much, but I remember even when she was dying, she was very near the end and I was not coping very well.

And I just remember lying with my head in her lap and she was stroking my hair and just saying, things about, it's not easy for us.

And things that were like, we, I get you.

I understand you.

Thanks to author Nadine J. Cohen for sharing her Nana and Zeida's stories of survival with me.

If this episode raised any issues, you can call Lifeline on 13 11 14, or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 46 36.

Grand Gestures is a Deadset Studios production for SBS Audio.

It's hosted by me, Lizzy Hoo.

The executive producer is Kelly Riordon, supervising producer is Grace Pashley, producers are Liam Riordan and Lucy McAfee.

Sound designed by Jeremy Wilmot.

Big shout out to the SBS team for their help, Caroline Gates, Joel Supple and Max Gosford.

Now, you can find Grand Gestures on the SBS Audio app or wherever you listen to podcasts, but you should go one step further.

Whip out your phone right now, find Grand Gestures in your app and hit follow.

It's completely free and it'll ensure you don't miss an episode.