Kiama, 120 kilometres south of Sydney, is known for its sand, surf and a world-famous blowhole.

But the town is also now a "dementia-friendly community" after it was selected to be a prototype location by peak body Dementia Australia.

At the library, there’s a frosted easy-to-read entry sign, substantial dementia resources, and signs in the toilets reminding users which way to turn the door handle.

The bigger difference, though, is in attitudes and understanding. At the Stone Wall Cafe, staff have been trained to speak slowly, give customers extra time and not ask them too many questions.

At the Stone Wall Cafe, staff have been trained to speak slowly, give customers extra time and not ask them too many questions.

Stone Wall Cafe, Kiama. Source: SBS News

A seniors exercise group has extra staff on hand to assist those participants with moderate levels of dementia.

“If it looks like they're confused or simply just not getting it, then we usually have a one-on-one person there with them,” physiotherapist Kate Watkins tells SBS News. “We run a lot of community education ... helping people to understand how the disease impacts on people’s brains and their sensory processing," says Nick Guggisberg of the Kiama Municipal Council.

“We run a lot of community education ... helping people to understand how the disease impacts on people’s brains and their sensory processing," says Nick Guggisberg of the Kiama Municipal Council.

Physiotherapist Kate Watkins assists Shirley at a dementia-friendly exercise class in Kiama. Source: SBS News

"But it’s about understanding the environment as well, looking for physical things that become confusing and distressing, and reducing them."

Segregation 'a breach of human rights'

Kiama’s aim of encouraging social inclusion is in stark contrast to the procession of horror stories heard at the aged care royal commission in Sydney this month that have focussed largely on the over-use of physical restraints within such facilities.

Dementia researcher Professor Richard Fleming of Wollongong University says authorities should also realise that “the built environment can be used as a form of restraint”.

Dementia support advocate Kate Swaffer told the royal commission last week that her late father-in-law spent his final years in a locked aged care ward.

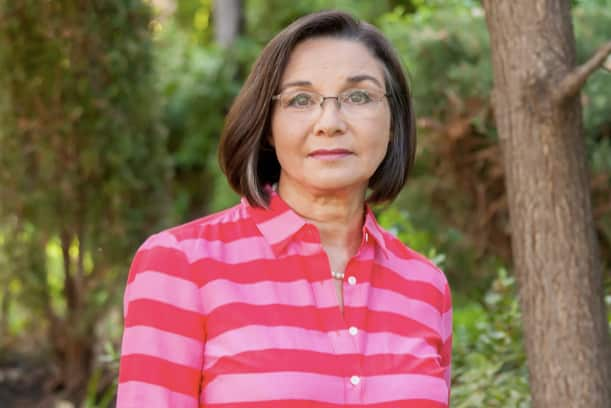

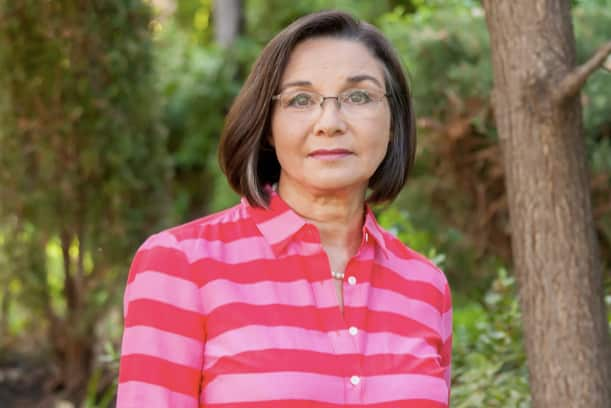

“He felt he had no freedom. Every single day we visited him, he asked us why we'd locked him in jail,” she told SBS News. Ms Swaffer - who herself was diagnosed with early onset dementia at age 49 - said: “I completely understand that some people need assisted living, but I don’t believe that institutions are the way forward and I completely believe that segregation is a complete breach of my and everyone else's human rights.”

Ms Swaffer - who herself was diagnosed with early onset dementia at age 49 - said: “I completely understand that some people need assisted living, but I don’t believe that institutions are the way forward and I completely believe that segregation is a complete breach of my and everyone else's human rights.”

Dementia support advocate Kate Swaffer. Source: Meg Hanson Photography

“We don't segregate people with intellectual disabilities or with mental illness or other physical disabilities anymore like we used to. We learned from institutions with orphans in them that institutional care generally breeds much worse care.”

Dementia-friendly design

In 2016, a Senate inquiry looked into the indefinite detention of people with cognitive and psychiatric Impairment.

The final report found detention was "a significant problem within the aged care context” and that it was "often informal, unregulated and unlawful”.

But the report made no recommendations on dementia. Some experts blame Australia's aged care facilities.

Some experts blame Australia's aged care facilities.

Source: The Village by Scalabrini

“Let’s face it, most of them were built more than 20 years ago” says Professor Fleming.

“Our knowledge of what makes a good environment for people with dementia has improved quite dramatically since.”

Some newer builds are taking heed of such research.

Professor Fleming, who is also the executive director of Dementia Training Australia, was a key advisor in the design of The Village by Scalabrini, a facility for those living with dementia and aged related care needs which opened last year in Drummoyne, in Sydney’s inner west.

Residents move around freely in its central piazza, which is comfortingly familiar, as around half of them are of Italian heritage.

A ‘nonna's kitchen’ offers a further boost to their confidence and competence. And inside the ‘casas’ - or apartments - there are no large, intimidating spaces; bedrooms have different-coloured doors that can be easily identified and residents can clearly see their bathrooms from their beds. “We provide a home-like environment that creates memory cues for residents’” said the facility’s chief executive Chris Grover.

“We provide a home-like environment that creates memory cues for residents’” said the facility’s chief executive Chris Grover.

Source: The Village by Scalabrini

“We provide things as simple as paintings that don't seek to encourage adverse behaviours but rather encourage good behaviours.”

“There's strong evidence that people who live in a well-designed environment have lower levels of agitation, depression and apathy, and lower use of medications,” Professor Fleming said.

Outside aged care, Dennis Frost sits on Dementia Australia’s Dementia Friendly Communities Advisory Group, and credits the “non-tokenistic” involvement of people living with dementia for Kiama’s success in eroding the stigma.

“There's also now enough businesses and people in the town that are really dementia-aware, that if you do have a problem you can ask.”

'Dementia villages'

Further afield, an alternative model starting to take hold is that of specific dementia zones or villages. One is currently under construction near Hobart.

Kiama Council has eschewed that approach.

“There are pros and cons with whatever strategy you choose to pursue,” said the council’s Mr Guggisberg.

“But a specific community designed for people living with dementia, in a sense isolates them further from the community. Our approach has always been to try to address the social implications of living with dementia. There are around 20 designated “dementia-friendly communities” around Australia, but Mr Frost believes change isn’t happening quickly enough.

There are around 20 designated “dementia-friendly communities” around Australia, but Mr Frost believes change isn’t happening quickly enough.

Kiama, NSW. Source: Supplied

Singapore and other countries, he says, have initiatives such as cafes, staffed entirely by people with dementia.

“I can’t see that being taken up in Australia at this stage … There’s still too much stigma and assumptions that need to be taken care of, such as trusting people with dementia with money.”

“And some of the clinical views I’ve seen in Australia … they still can’t accept there’s anything to dementia other than that there’s a loss of memory and an early demise”.